The slippery slope to Tiananmen Square

Contextualizing What Happened on January 4, 1989

By Navin

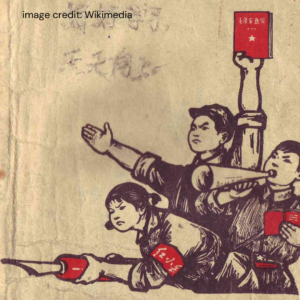

As the People’s Republic of China entered the modern age, it was still operating by Mao Zedong’s Communist principles, on which it was founded. However, there was a nationwide shift in Chinese sentiment going into the 1970s and 1980s. The Chinese people felt that they were being left behind by the rest of the world – globalization and industrialization were not yet widespread in China. As a result, demands for change began to ripple through the populace, stemming especially from students and former Red Guards (college students tasked to aggressively support Mao’s policies) who were learning more about other forms of government  and political philosophies. Drawing from aspects of socialism, liberalism, capitalism, and democracy, students and the public began to advocate for more freedom and an end to corruption.

and political philosophies. Drawing from aspects of socialism, liberalism, capitalism, and democracy, students and the public began to advocate for more freedom and an end to corruption.

So… what could have been the spark that led to the protests and massacre on Tiananmen Square?

Historians agree that a turning point was the death of former CCP Chairman and Secretary Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989. Yaobang had been a particularly liberal leader of the party, supporting freedom of speech, transparency of the press, and economic free markets; he had also been tolerant of student protests in 1986. His democratic ideals held appeal among students.

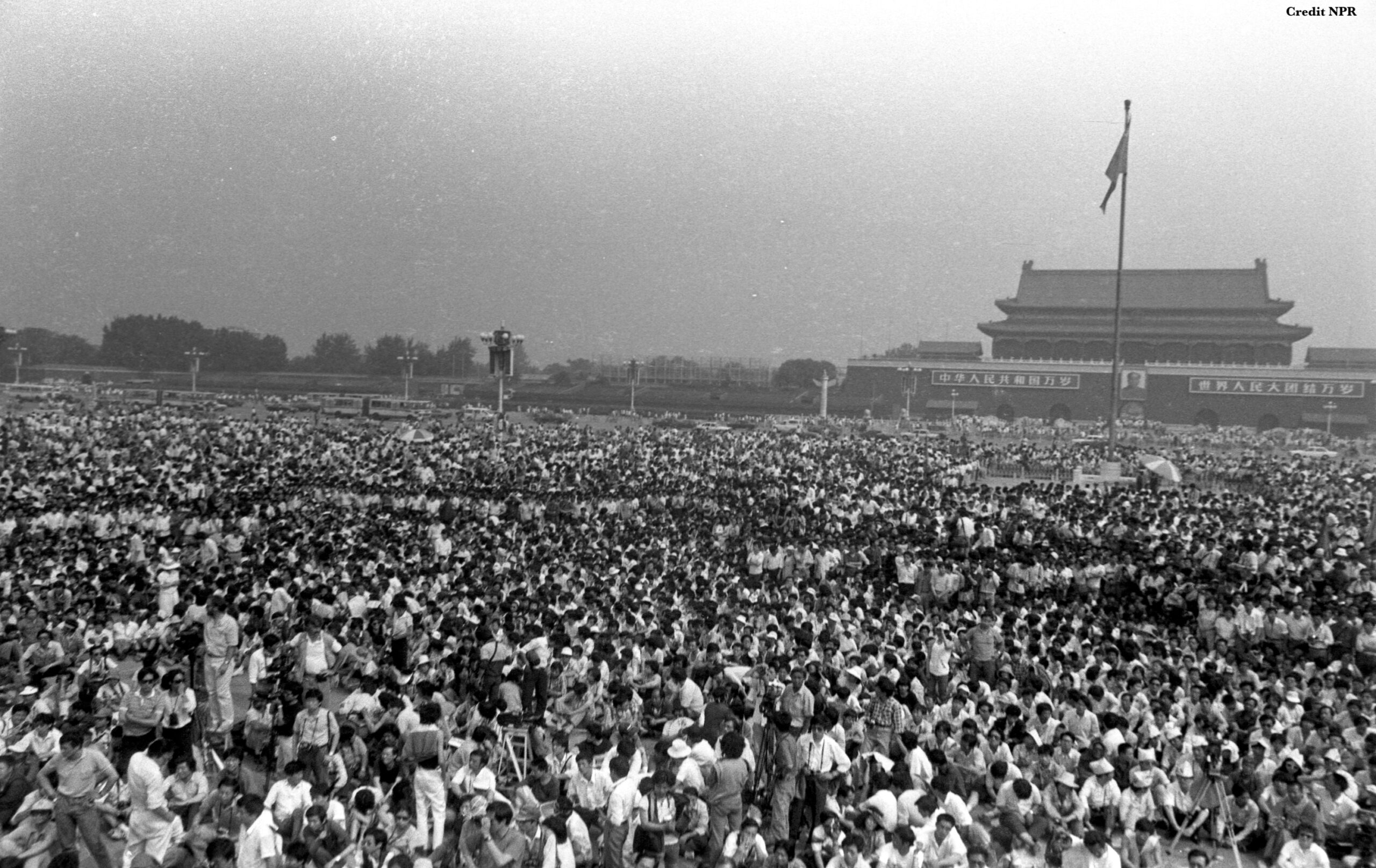

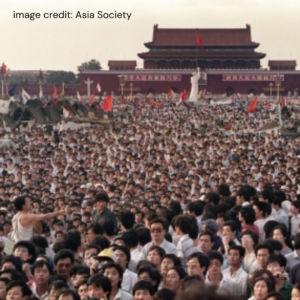

On April 17, 500 students held a memorial for Yaobang in Tiananmen Square, a 500,000-capacity city center in Beijing. The police, fearing a riot, dispersed the crowd. And with that, everything snowballed.

News of this spread through the city, angering other students. This set a precedent for the rest of the conflict – the students would gather, the police would violently rebut their protests, and more students would join together. This escalation resulted in what had been a remembrance for Yaobang turning into a movement for a more democratic republic and an end to corruption.

The students tried to present a list of grievances to the Committee of the party on April 20. Despite their peaceful efforts, they were violently dispersed by police with batons. In response, 100,000 protestors marched to Tiananmen Square. On April 26, the government-owned newspapers printed headlines, stating that the students were creating civil unrest and plotting to overthrow the government.

The students tried to present a list of grievances to the Committee of the party on April 20. Despite their peaceful efforts, they were violently dispersed by police with batons. In response, 100,000 protestors marched to Tiananmen Square. On April 26, the government-owned newspapers printed headlines, stating that the students were creating civil unrest and plotting to overthrow the government.

In response, students at 40 universities began striking. The discontent boiled over into May 1989, and 3000 students began a hunger strike on May 13. Leader of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev was scheduled to visit China on May 15, and the protesters hoped that the increased media presence would draw international eyes to their struggle. As momentum picked up, over 1,000,000 citizens were demonstrating across Beijing. The government declared martial law, as the movement became overwhelming. Zhao Ziyang, Secretary General of the CCP, was one of the party’s more liberal leaders. He delivered an impassioned speech at the Square, begging students to stop the hunger strike, and even weeping. Nevertheless, the resolve of the demonstrators remained strong, and the protests continued into June. In the first week of June, the government cracked down. Foreign journalists’ access was cut off, tanks and soldiers were mobilized, and finally, on June 3rd, soldiers were ordered to clear the square at all costs.

The military used tear gas, batons, and riot gear to fight their way into the city, and by midnight on June 3rd, they had reached the square. On June 4th, the military opened fire on protestors, and the crowds were scattered. By the end of the day, over 10,000 were injured, and the death toll is estimated to be in the several hundreds or several thousands.

Censorship has long been a hallmark of totalitarian regimes, and the Tiananmen Square Massacre remains one of the most censored and contentious events in  modern history. Official Chinese accounts minimize the casualty figures and portray the tragedy as a turning point that secured the stability of contemporary China.

modern history. Official Chinese accounts minimize the casualty figures and portray the tragedy as a turning point that secured the stability of contemporary China.

However, beneath the state-controlled narrative lies the undeniable truth of the protesters’ sacrifices. Their bravery and resolve, as they risked everything in their fight for democracy, continue to resonate as a timeless testament to the human spirit’s pursuit of freedom.

🎓