Wildlife Corridors

It’s raining heavily as I write this, but this rain only serves to make me appreciate the greenery better. As the climate changes rapidly with American cities (and for that matter, cities around the world), trees and green spaces become more important than ever; trees sequester carbon, and green spaces mitigate heat. An important factor in the ability of any ecosystem to thrive is the presence and safety of the animals that make up that ecosystem.

Any ecosystem will be affected by the world around it; nature and surroundings will inevitably put pressure on any ecosystem. An ecosystem’s resilience is its ability to respond to pressure and return to a balanced equilibrium. The more diverse an ecosystem is, the more likely it is to be able to return to equilibrium. Encouraging biodiversity is vitally important to happy, safe communities for this reason.

When we build roads and developments through natural spaces, we’re breaking ecosystems up into parts separated by terrain that’s unfriendly to animals. This division is called landscape fragmentation. Animals native to a fragmented area aren’t given time to leave or find a safer home. Instead, their space is suddenly limited – often leaving them without enough room to find food, migrate, or reproduce. Roads are fatal for such animals to cross, as is evidenced by the roadkill that heartbreakingly is scattered over our highways. The animals aren’t aware that they suddenly have to stop migrating where instinct tells them they can. At the same time, we’d be hard-pressed to admit that we want bears wandering our streets alongside the children of our neighborhoods.

Connectivity is the key to a future conducive to these animals’ success in a changing wild.

Animals as diverse as deer, panthers, and the monarch butterfly need undivided space to survive and thrive.

This is where wildlife corridors come in. Animals that need to migrate accordingly need an avenue over which to pass to their usual spaces. Reserving space in the form of national parks and conservation zones is successful to some extent, stopping development in clearly delineated locations. Parks don’t change an animal’s ability to migrate over a fragmented zone, however.

This is where wildlife corridors come in. Animals that need to migrate accordingly need an avenue over which to pass to their usual spaces. Reserving space in the form of national parks and conservation zones is successful to some extent, stopping development in clearly delineated locations. Parks don’t change an animal’s ability to migrate over a fragmented zone, however.

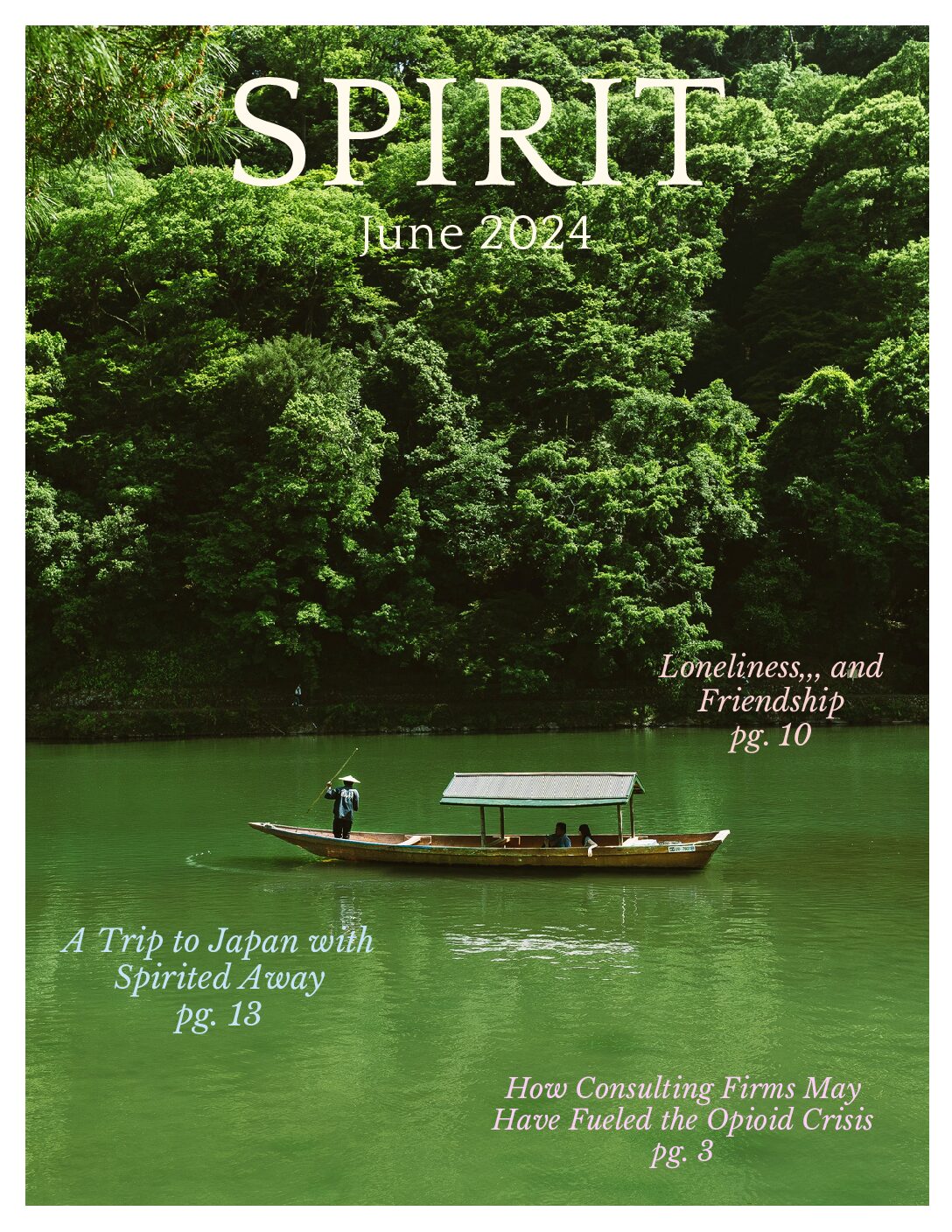

A wildlife corridor, as pictured here, is a strip of land that bridges fragmented habitats, covered by the same vegetation and floral cover as the land around. This can serve as a “traveling avenue” for migrating animals and connect other tracts of land. Wilderness corridors need to be a significant width, allowing animals enough space to nest and rest, as it were. A well-vegetated wilderness corridor can allow animals to find food or even escape cover as well as acting as bridges for native plants needed for a species to thrive.

Wilderness corridors can be built as overpasses on highways, and as underpasses; they can be built bridging two sides of a river or as a crossing on a highway in the desert. According to the Indiana state government, wilderness corridors can allow for “the wildlife on private [to be] greatly enhanced for wildlife use.” Advantages include: use of wilderness corridors as “greenbelts” in urban spaces, decreased heating and cooling costs, increased biodiversity, and increased “movement between isolated populations.” Simply put, it’s a neat solution for a problem that affects every corner of the US and much of the world. Nature affects us all; it’s our duty to steward this planet well and long.